new to the gluten free journey?

new to the gluten free journey?

Under healthy conditions, the GI tract breaks down our food, absorbs nutrients for energy, and expels waste. But when villous atrophy occurs, the normal function of the gut is compromise, and severe health consequences can ensue.

Read on to find answers to questions like:

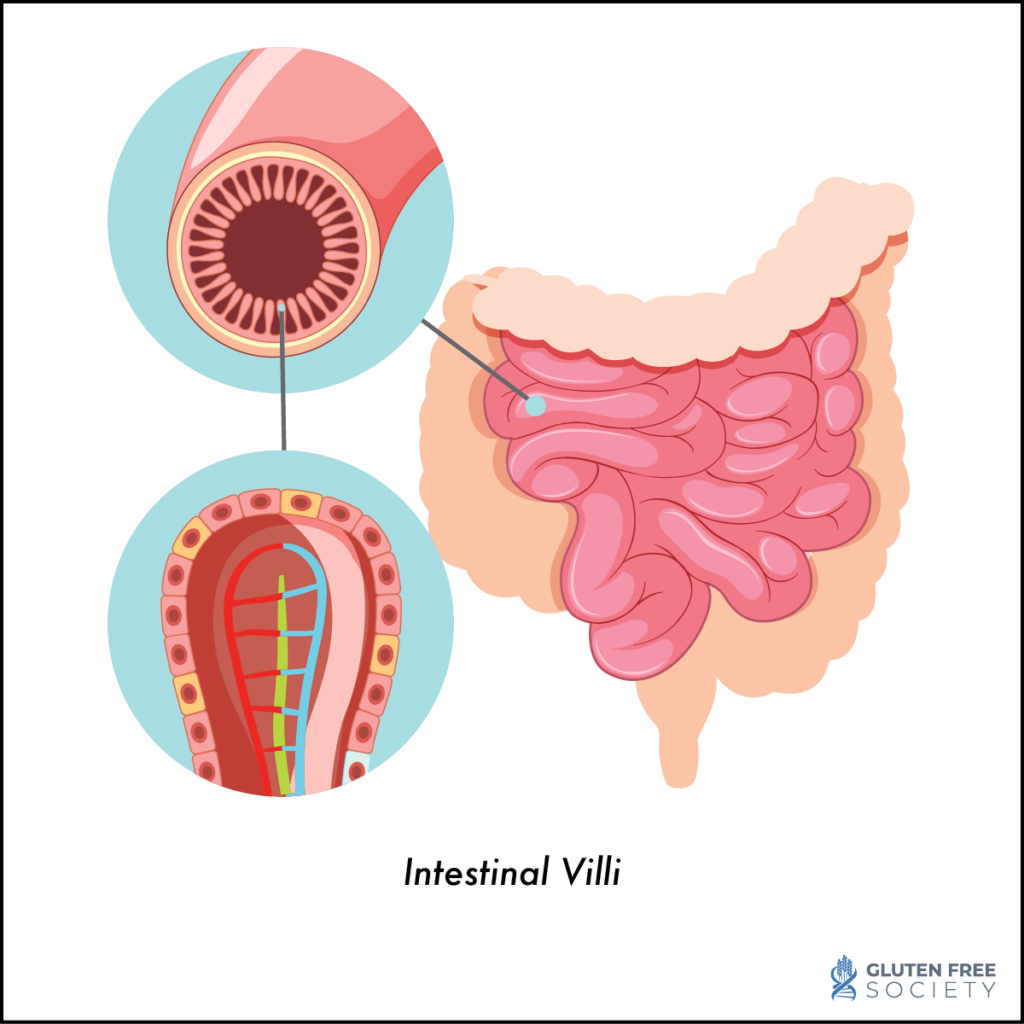

To answer this question let us first define villi. Villi are small, finger-like projections that line the small intestine and are connected to blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. They function to increase the surface area of the small intestine’s walls, which allows for greater absorption of nutrients from food. Villous atrophy is a condition in which the intestinal villi are destroyed or damaged.

To answer this question let us first define villi. Villi are small, finger-like projections that line the small intestine and are connected to blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. They function to increase the surface area of the small intestine’s walls, which allows for greater absorption of nutrients from food. Villous atrophy is a condition in which the intestinal villi are destroyed or damaged.

This can lead to a range of complications and symptoms within the body.

Villous atrophy is a key characteristic finding in celiac disease. It is caused by gluten exposure; however, villous atrophy has other causes (discussed below).

The nutrient deficiencies caused by villous atrophy can affect just about every system in our body. This is why the symptoms of villous atrophy are numerous, and commonly misdiagnosed as other conditions.

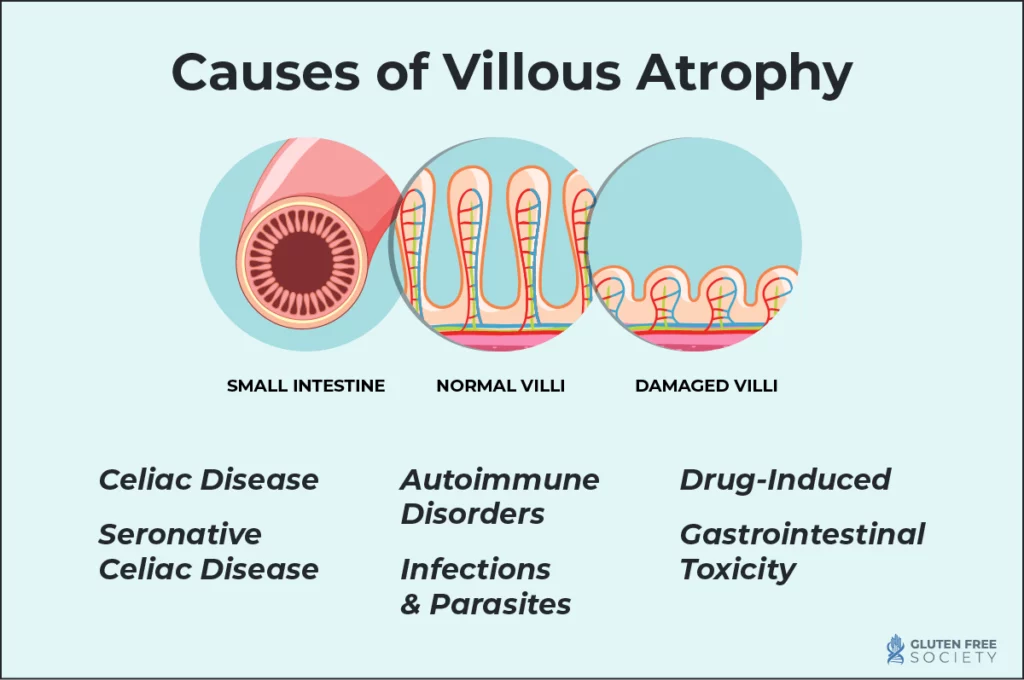

Villous atrophy is most commonly caused by celiac disease, but it isn’t the only cause. When villous atrophy occurs in patients without celiac disease, it is referred to as “seronegative enteropathy.” Several possible causes of villous atrophy are detailed below.

Celiac disease is the best-known cause of villous atrophy. When people who have celiac eat foods that contain the gluten protein, it triggers an attack by the immune system. This attack affects the intestinal villi, flattening them and rendering them unable to perform their function properly. Certain other factors may increase the severity of villous atrophy, including use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Seronegative celiac disease is when a person has negative anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibodies but presence of villous atrophy and uneven brush border associated to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotype DQ2 and/or DQ8.

Other autoimmune disorders can also cause villous atrophy. For example, Crohn’s disease is the second most common cause of villous atrophy after celiac disease. Common symptoms include chronic diarrhea with blood or mucus in the stools, weight loss, and abdominal pain. These symptoms may be similar to celiac disease for some patients, and the conditions may coexist.

Other autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) I may also generate oxidative stress in the gut that can impact intestinal villi.

Certain infections can cause villous atrophy. For example, Giardia is a common food- and waterborne parasite, and E. coli and salmonella are bacterial pathogens that cause a spectrum of effects, including villous atrophy.

Certain drugs can damage the small intestine, which can affect the function of the intestinal villi. Mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, methotrexate, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are some of the medications known to cause damage to intestinal villi.

Foreign and endogenous chemicals, such as food additives and contaminants, environmental toxins, and pesticides, can produce gastrointestinal toxicity by a number of mechanisms. In addition, mycotoxins from food and environment can also find their way into the body and result in alterations in normal function.

There are a number of signs and symptoms of villous atrophy. They may be digestive in nature, or “extra intestinal”, meaning they affect other parts of the body, outside of the digestive tract.

Digestive Symptoms

Common digestive symptoms include diarrhea, bloating, cramping, and gas.

Nutritional Deficiencies

When the small intestine is not functioning properly, it cannot absorb nutrients. Common deficiencies that are caused by poor nutrient absorption in the small intestine include iron, zinc, folate, vitamin B12, and more. Nutritional deficiencies can also further impair gut health, feeding a vicious cycle of nutrient deficiencies and impaired gut health.

Extraintestinal Symptoms

Other symptoms that occur outside of the digestive tract include the following:

Asymptomatic Cases

There are some cases in which villous atrophy occurs without noticeable symptoms. This is sometimes referred to as silent celiac disease.

Villous atrophy is typically diagnosed through endoscopic biopsy. However, other tests should be performed to understand the root cause of villous atrophy so that they can be properly treated.

Endoscopic Biopsy

An endoscopic biopsy is performed by putting a long, thin tube down the throat for exploration. The tube, called an endoscope, has a close focusing telescope on the end for viewing and can obtain a small amount of tissue for study.

Serological Tests

Certain blood tests measure the body’s response to gluten and can provide supporting evidence as to the cause of villous atrophy. There are several different types of blood tests, but each one relies on measuring specific types of antibodies – IgA or IgG:

Learn more about these tests and other tests for celiac disease in this article.

Differential Diagnosis

Since many different conditions can share similar symptoms as villous atrophy, your provider may perform testing or ask questions to rule out other possible conditions that could be causing your symptoms.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing is a highly accurate look at your genes to understand whether you have a genetic predisposition to reacting to gluten. While this won’t confirm whether or not you have villous atrophy, or the cause of villous atrophy, it can provide valuable information as to whether you are genetically predisposed to celiac disease. If you are, it is likely that gluten could be contributing to villous atrophy.

You do not need to be eating gluten in order to get an accurate test result. However, research indicates that clinical manifestations, like those found through blood testing and endoscopy, are not sufficient for a true diagnosis. A genetic test shows a more complete picture. Make sure to get a test that measures for all genes linked to gluten sensitivity (HLA-DQ1/HLA-DQ3) and celiac disease (HLA-DQ2/HLA-DQ8). Some tests only check for genes linked to celiac disease.

The good news is that treatment and management of villous atrophy can be done largely on your own through diet and lifestyle modifications. If your atrophy is being caused by gluten, then the first step is obviously a diet change.

Gluten-Free Diet

A strict gluten-free diet is required for reversal of villous atrophy in the small intestine. While some symptoms may resolve within days or weeks of adopting a gluten free diet, full healing of the small intestine may take months or even years.

While a gluten free diet might seem straightforward, the unfortunate reality is that many products are marketed as gluten free when they actually contain hidden sources of gluten. Therefore it is critical to understand how to read labels and what to look for so that you can properly avoid gluten in your diet. Plenty of nutritious and delicious foods exist that are naturally gluten free, and fortunately, they are typically better for your health than their gluten containing counterparts.

Addressing Nutritional Deficiencies

It is also important to correct any nutrient deficiencies through targeted supplementation and specific dietary changes. We recommend getting tested for nutritional deficiencies, as accurate test results can help guide your decisions around food choice and supplementation.

Medications

Certain medications can contribute to villous atrophy. It is important to discuss the need to discontinue any of these medications (or find a suitable replacement) in order to allow healing of the intestinal lining.

You should also speak with your doctor to discuss the possibility that your medication(s) could contain hidden gluten. Any gluten containing medicines could hinder your ability to recover.

Follow-Up and Monitoring

When trying to heal from villous atrophy and engaging in a gluten free lifestyle, it is important to work with a healthcare professional who is well versed in celiac disease and villous atrophy. A practitioner may perform additional testing and can discuss personalized treatment options and strategies to help you heal and optimize your health. A professional will also be a guide along the journey so that together you can monitor progress and make adjustments to your treatment plan as needed.

Villous atrophy will not resolve on its own, and left unchecked, it can result in further health complications, including the following:

Diet and Lifestyle Modifications

Even after eliminating gluten from your diet, there is healing that must occur “behind the scenes”. This healing will address the intestinal damage from gluten consumption, plus the downstream effects of intestinal damage, like compromised skin health and nutrient deficiencies. Below are some ways to help promote healing.

Support Networks

Making lifestyle changes can feel daunting and isolating. Finding support groups or communities for individuals with villous atrophy or who are adopting a gluten free lifestyle can help tremendously. Support groups may be found locally through healthcare facilities, local practitioners, and health communities, but many patients find support online as well.

In addition, make your friends and family aware of your condition so that they can support the diet and lifestyle changes that you need to make. Provide context to help them understand what it is, why you’re doing it, and what it means for how you may interact with them. This can help make things like family gatherings or eating out at restaurants less stressful.

Villous atrophy is a condition in which the intestinal villi are destroyed or damaged. When intestinal villi are atrophied and not working properly, it prevents the body from absorbing nutrients from food. This can lead to a range of complications and symptoms within the body.

Digestive symptoms like diarrhea, bloating, cramping, and gas, but symptoms may also occur in other parts of the body, like the skin, joints, bones, and brain.

If you think you may be experiencing villous atrophy, reach out to a healthcare practitioner who is well versed in this condition for proper testing and accurate diagnosis. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the long term health outcomes.

Still have questions? Here are answers to some of the most commonly asked questions around villous atrophy.

What is the difference between celiac disease and villous atrophy?

Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition that is triggered by the ingestion of gluten, a protein found in grains like wheat, barley, and rye. Gluten proteins trigger inflammation in the intestinal tract and other parts of the body. This systemic inflammation can then contribute to the development of autoimmune disease and a host of other health issues.

Villous atrophy is just one of the effects of celiac disease. While villous atrophy is often caused by celiac disease, it can have other causes.

Can villous atrophy be reversed?

Villous atrophy can be reversed, but some cases may not be reversed. A study conducted at the Mayo Clinic reviewed intestinal biopsy records for 241 adults who’d been diagnosed with celiac disease, and who then had a follow-up biopsy.

Over 80% of patients with celiac disease had experienced improvement in their celiac disease symptoms, but after two years, their biopsies showed that only about one-third of these patients had intestinal villi that had recovered fully. After five years, about two-thirds had fully recovered intestinal villi.

Sometimes a condition called refractory celiac disease is diagnosed in patients that fail to recover from a gluten free diet.

How long does it take for the villi to heal after starting a gluten-free diet?

Healing time varies by person, and biopsy is the only way to evaluate mucosal healing. Some of the variance can be due to different levels of adherence to a strict gluten free diet, and how long damage was present before identified, but some variance is unexplained. Some people will heal within a year, others may take several years. Younger patients tend to heal more quickly than older patients.

Is villous atrophy always related to gluten?

Villous atrophy is most commonly related to gluten, but it is not always related to gluten. Infections, parasites, toxins, and medications can all contribute to villous atrophy.

What should I do if I think I have villous atrophy?

If you think you may have villous atrophy, it is important to find a healthcare provider who is experienced in diagnosing and treating this condition, including everything discussed in this article. Gather a list of your symptoms and don’t be afraid to ask questions of any provider you consider working. If you feel a provider is not listening to your concerns, respectfully move on to find another provider.

Stay up-to-date with the latest articles, tips, recipes and more.

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

If you are pregnant, nursing, taking medication, or have a medical condition, consult your physician before using this product.

The entire contents of this website are based upon the opinions of Peter Osborne, unless otherwise noted. Individual articles are based upon the opinions of the respective author, who retains copyright as marked. The information on this website is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice. It is intended as a sharing of knowledge and information from the research and experience of Peter Osborne and his community. Peter Osborne encourages you to make your own health care decisions based upon your research and in partnership with a qualified health care professional.