new to the gluten free journey?

new to the gluten free journey?

Contents

ToggleMany wonder…Does gluten affect autism? Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD or autism) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized primarily by deficits in social communication and interaction and by restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior. As the name implies, its range of symptoms exist on a spectrum and vary widely in severity.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, autism affects an estimated 1 in 54 children in the United States today. A growing body of research is examining connections between autism and dietary interventions. While a number of special diets have been suggested as beneficial in autism, gluten has received particularly close attention as a potentially exacerbating factor.

Several studies as well as anecdotal reports suggest a beneficial effect of a gluten-free diet in helping to mitigate some of the behavioral and intellectual challenges associated with autism.

However, both caregivers and clinicians have expressed an uncertainty of the value of a gluten-free diet in those with autism. Adopting a gluten-free diet can be a significant change, particularly in children, and even more in children who often have sensory processing challenges that limit acceptable tastes and textures.

So we’re digging into this question, can a gluten-free diet help with autism? That answer is a bit complicated, but here’s what we know.

Celiac disease has been studied in connection with autism and comorbidity (the simultaneous presence of two or more diseases or medical conditions in a patient) has been established in several studies.

Gluten and autism have a number of potential connections. Numerous studies have identified higher gluten based antibody markers in patients with autism. Gluten is known to affect the intestinal barrier leading to leaky gut (intestinal permeability) and permeability of the blood brain barrier (leaky brain). Research has identified that children diagnosed with autism have a higher incidence of leaky gut and leaky brain. Additionally, studies have linked gluten’s role in damaging the blood vessels of the brain and contributing to damage of different protein structures in the brain.

With a body of evidence supporting a comorbidity between autism and celiac disease, studies have emerged to investigate what drives this connection. Of particular curiosity is the shared experience in both conditions of non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, constipation, and bloating. Most research around a connection is based on the hypothesis that celiac disease and autism are both in some associated with heightened immune responses or autoimmunity, but this connection is still being actively studied.

Gluten-free diets are often combined with casein-free diets in both research studies and in practice by parents looking for ways to support their children. While several studies have shown that gluten-free diets can be helpful in autism, the research can be contradictory. Overall, studies evaluating the definitive effects of a gluten-free diet on autistic symptoms for all children and cases have so far been inconclusive.

The reason that research around benefits is mixed can be for a variety of reasons. For example, a gluten-free diet alone may not address all of the dietary needs (deficiencies, toxicities, etc.) that a child faces. So while a gluten-free diet may help, there may be other confounding factors that are still contributing to symptoms and masking any potential benefits. In addition a gluten-free diet may not be strictly followed, either due to misunderstanding around what is allowed or hidden sources of gluten, or to difficulty getting children with very strong preferences and limited diets to comply. Furthermore, results are generally self reported by caregivers, so errors can occur and there is no way to fully eliminate a placebo effect as study participants (or their parents) know whether or not they are following a new diet.

However, there is still compelling evidence that a gluten-free diet can improve symptoms of autism. One study of 50 kids found improvements in sleep, attention, hyperactivity, and anxiety/compulsion on both a gluten-free only and a combined gluten-free and casein-free diet.

Another study of 387 subject pairs (children with autism and their caregivers) that specifically reported strict diet implementation, indicated by complete gluten and casein elimination and infrequent diet errors, reported improvement in autism behaviors, physiological symptoms, and social behaviors.

However, another study consisting of two small randomized controlled trials found three significant treatment effects in favor of a gluten-free diet intervention. The study found improved overall autistic traits, social isolation, and overall ability to communicate and interact. These results are promising enough to merit further research into the possible benefits of gluten free diets for autism.

Despite some mixed reports in research, both gluten-free and casein-free diets are quite common diets to try. Many parents are eager to find a way to support their children, and nutritional changes are relatively easy and risk-free ways to test out potential benefits. In fact, a 2015 UK survey reported that more than 80% of parents of children with autism reported some kind of dietary intervention for their child. A gluten-free and casein-free diet was reported in 29%. When asked about the effects of the gluten-free and casein-free diet, 20-29% of the parents reported significant improvements on the autism spectrum disorder core dimensions, particularly gastrointestinal symptoms, concentration, and attention.

While the benefits of a gluten-free and casein-free diet are debatable, it is less debatable that nutrition in general and autism symptoms are linked. As one study concluded, gluten-free, casein-free, and ketogenic diets can play a role in alleviating autism symptoms. However, even on these diets, consumption of sugar, additives, pesticides, genetically modified organisms, inorganic processed foods, and hard-to-digest starches may aggravate symptoms.

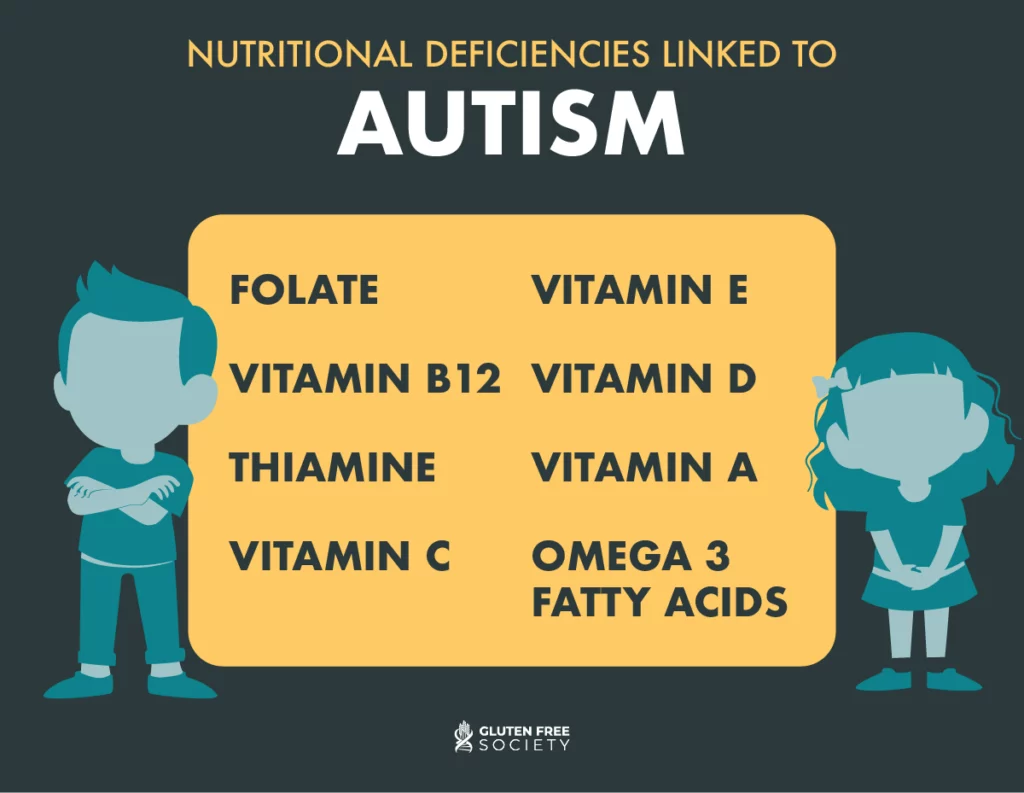

Children with autism are usually particularly selective eaters which can contribute to nutrient deficiencies. Thus, the risk for the nutritional deficiencies in children on restricted diets remains an area of scientific interest. In addition, several researchers have noted that patients with autism often have various metabolic and nutritional abnormalities including issues with sulfation, methylation, glutathione redox imbalances, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction that can impact absorption of nutrients. These deficiencies can further exacerbate autism symptoms. Common deficiencies linked to autism include:

But just because deficiencies are common doesn’t mean that children should blindly supplement. In fact, one study found that even in children who supplement, almost one-third remained deficient in vitamin D and up to 54% for calcium. This suggests that the issue may be absorption rather than intake. In addition, in many cases, supplementation led to excess vitamin A, folate, and zinc intake across the sample, plus vitamin C and copper among children aged 2 to 3 years, and manganese and copper for children aged 4 to 8 years. The takeaway? Don’t guess what deficiencies exist, get tested to know for sure so that you can target supplementation accordingly. And if deficiencies still exist after testing, you likely need to dig further into why those nutrients aren’t being properly absorbed.

It turns out that it may not just be a child’s diet once outside the womb and eating solids that can impact development of autism. Rather, a mother’s diet and supplementation while pregnant can impact growth and development and contribute to autism or improve autism with supplementation. Even if a mother’s diet is complete and a prenatal vitamin is taken consistently, she may experience gluten-induced nutritional deficiencies as a result of undiagnosed celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

One study of 273,107 mother-child pairs aged 4-15 in Stockholm, Sweden found maternal multivitamin use (with or without additional iron or folic acid) throughout pregnancy was associated with lower odds of autism with intellectual disability in children compared with mothers who did not use multivitamins, iron, and folic acid. It concluded that maternal multivitamin supplementation during pregnancy may be inversely associated with autism with intellectual disability in offspring.

Another population-based case-control study showed that mothers of children with autism took prenatal vitamins before pregnancy less often than those of neurotypical children. An increased risk of autism was also found for children of mothers who had certain gene variants related to the metabolism of vitamins with no vitamin intake during pregnancy.

The following nutrients are particularly important for a pregnant women and her baby during the prenatal period with respect to potential autism risk later in life:

Gluten is certainly not the only type of allergen that can exacerbate the risk of developing or symptoms of autism. A number of foods, such as dairy and casein, can cause an inflammatory response and cascade of symptoms within the body.

In addition, several environmental factors have been linked to the risk of autism. These include exposure to environmental toxins, heavy metals (particularly lead and mercury), and certain endocrine disrupting chemicals (such as those in many household cleaners, personal care products, and flame retardants used on clothing and furniture.

Several studies have also linked an imbalance in the good and bad bacteria in the gut (gut dysbiosis) to autism. The gut-brain interaction is being actively studied with respect to autism and shows promise for understanding more about potential causes and therapies to manage symptoms. Another study even suggested that microbiota transfer therapy can alter the gut microbiome and improve GI and behavioral symptoms of autism. This research provides substantial encouraging evidence to investigate gut dysbiosis as part of an array of therapies to understand and manage autism.

While the link between gluten and autism is still being heavily studied, it is well established that nutrition and food are potential triggers and compounding factors of autism symptoms. Evaluating diet and nutritional status in both pregnant women and their children should be a key component in the treatment of prevention of autism. I recommend that all children with neurodevelopmental problems be assessed for gluten and other food sensitivities, nutritional deficiency and malabsorption syndromes alongside medical and psychological interventions.

Stay up-to-date with the latest articles, tips, recipes and more.

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

If you are pregnant, nursing, taking medication, or have a medical condition, consult your physician before using this product.

The entire contents of this website are based upon the opinions of Peter Osborne, unless otherwise noted. Individual articles are based upon the opinions of the respective author, who retains copyright as marked. The information on this website is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice. It is intended as a sharing of knowledge and information from the research and experience of Peter Osborne and his community. Peter Osborne encourages you to make your own health care decisions based upon your research and in partnership with a qualified health care professional.